CASE REPORT | https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10055-0052 |

Congenital Tuberculosis: A Challenging Diagnosis

1,2Department of Pediatrics, Sri Guru Ram Das Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Amritsar, Punjab, India

Corresponding Author: Karuna Thapar, Professor and Head, Department of Pediatrics, Sri Guru Ram Das Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Amritsar, Punjab, India, Phone: +91 9815518330, e-mail: kthapar2000@yahoo.com

How to cite this article Thapar K, Garg A. Congenital Tuberculosis: A Challenging Diagnosis. Curr Trends Diagn Treat 2018;2(2):118-120.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Congenital tuberculosis though rare is of paramount importance to outline early management. Symptoms of congenital tuberculosis may be present at birth but more commonly begin by second or third week of life. The clinical presentation of tuberculosis in newborns is similar to that caused by sepsis and other congenital infections.

Purpose: Nonspecific nature of the disease in the newborn infant and less knowledge of the maternal disease prior to delivery makes the diagnosis a clinical challenge.

Case report: A rare case of one and a half month F baby who had fever since 3 weeks of age, after a month baby landed into neonatal intensive care unit because of missed diagnosis and reported to us with clinical signs of sepsis.

Investigations and results: X-Ray chest was suggestive of tuberculosis, presumptive diagnosis of tuberculosis made and baby started on anti tubercular therapy. Cartridge based nucleic acid amplification test was found positive in gastric aspirate. The baby started recovering and during that period mother developed symptoms of low grade fever, lethargy, headache and seizures. She was diagnosed as neurotuberculosis with evidence of multiple tuberculomas in MRI-Brain. This led to confirmation of diagnosis of congenital tuberculosis.

Conclusion: Most important clue for rapid diagnosis of congenital tuberculosis is maternal history of tuberculosis. Often, the mother's disease is discovered after the neonatal diagnosis is suspected. In summary, there is need to improve screening to identify and treat active tuberculosis in prenatal period, which decreases perinatal mortality and prevents occurrence of this serious disease in neonate. This case remarks difficulties on diagnosis and therapeutic management about this important severe disease in public health, and alert for development of protocols that foresee these difficulties.

Keywords: Anti tubercular therapy, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, Cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test, Tuberculosis.

CASE REPORT

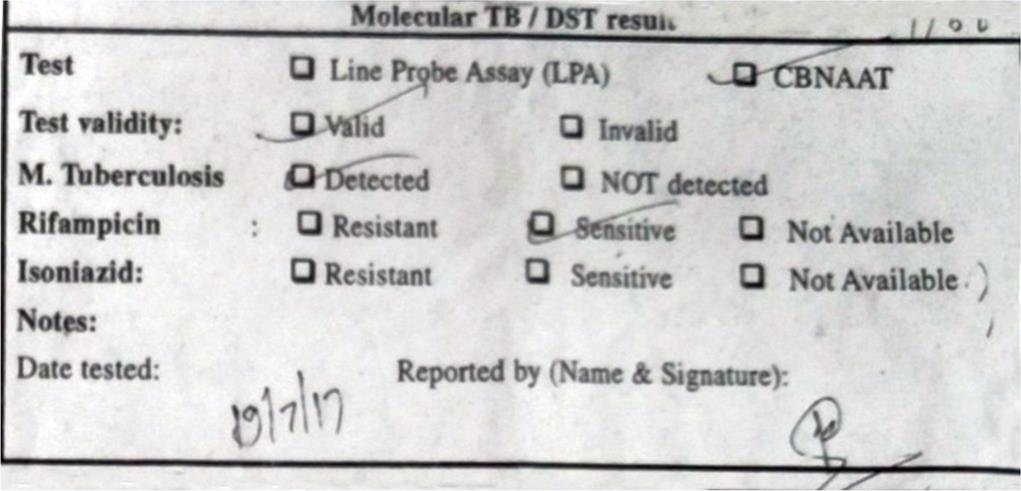

A one and a half month old female baby presented with a history of fever since 3 weeks of age. Antenatal history was uneventful except mother being hepatitis B positive. Baby was the second in birth order, full-term normal vaginal delivery at a private nursing home, cried immediately after birth, and vaccinated for bacillus calmette-guerin (BCG), hepatitis B along with its immunoglobulin within 24 hours, top-fed, no history of contact, neonatal jaundice, or vertical infection. She was treated for 2 weeks as an outpatient by a practitioner and the baby deteriorated, developed respiratory distress, refusal to feed, and was quite sick, so shifted to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in a private nursing home. The baby was investigated and treated with many antibiotics for sepsis. The baby did not show any improvement. Parents left against medical advice and reported to us. On examination, the baby was pale with a heart rate of 166/min, a respiratory rate of 68/min; on pulse oximetry, O2 saturation was 90%; no cyanosis, icterus, pedal edema, and congenital anomaly. The weight of the baby was 3.2 kg and the rest anthropometry was within normal limits. The respiratory system revealed subcostal, intercostal recessions, flaring of alae nasi, and on auscultation, bilateral crepitations were present. The cardiovascular system was normal. There was hepatosplenomegaly, a liver span was 8 cm, and kidneys were not palpable. While taking the blood sample, the baby had a cardiac arrest, resuscitated, and was put on ventilator support for 3 days. Investigations revealed Hb—10.4 gm/dL, TLC—19,000/mm3; chest X-ray (Fig. 1) shows bilateral patchy infiltrates; cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test (CB-NAAT) was positive (Fig. 2); liver function, renal function tests, electrolytes, random blood sugar, and serum calcium were within normal limits. Blood and urine cultures were negative. No acid fast bacillus (AFB) was seen on gastric lavage. The culture for AFB was negative. All contacts were screened for tuberculosis (TB) and none were positive. Child was treated with vancomycin and meropenem for sepsis in the beginning along with antitubercular therapy (ATT) presuming TB. Full supportive therapy was given. Gradually, child improved and was off O2 after 1 week with an evidence of improvement on chest X-ray (Fig. 3). The baby was discharged after 11 days of stay in NICU accepting full feed, and weight was gained with normal vitals. Mother complained lethargy, anxiety, and fever since 1 month, chest X-ray and montoux were negative, she refused endometrial biopsy. After 1 week, she complained of severe headache, MRI of brain showed multiple tuberculomas, developed seizures, hospitalized, and treated with ATT, steroids, and antiepileptics. A week later, she developed paraplegia and MRI of spine showed spinal TB, referred to a higher center by the treating physician. Diagnosis of congenital TB was confirmed when the mother developed neurotuberculosis. The baby recovered completely after 6 months of therapy.

Fig. 1: X-ray chest PA view shows bilateral infiltrates

Fig. 2: CBNAAT showing positive result from directly observed therapy (DOT) center

Fig. 3: X-ray chest PA view shows improvement after antitubercular therapy within 1 week therapy (DOT) center

DISCUSSION

Perinatal TB in the neonate can be either congenital or neonatal. The only criterion for distinguishing congenital TB from postnatal acquired TB was first proposed by Beitzke in 1935 and revised by Cantwell et al. in 1994.5 According to the revised criteria, the infant must have proven TB lesions and, at least, one of the following: (i) lesions present in the first week of life; (ii) a primary hepatic complex or caseating hepatic granulomas; (iii) TB infection of the placenta or the maternal genital tract; or (iv) exclusion of the possibility of postnatal transmission by a thorough investigation of contact. Making an early diagnosis of TB in an infant is difficult as symptoms usually begin early (2–4 weeks), which mimic bacterial sepsis and other congenital infections.6 Besides, the median age of presentation of congenital TB is 24 days (range, 1–84 days), and the median age of diagnosis of TB in infants is 8 months (range, 3.5–12 months).5,8 Hepatomegaly (76%), respiratory distress (72%), fever (48%), and lymphadenopathy (38%) are the most common symptoms and signs of congenital TB.5 In our case, the majority of symptoms were present and chest X-ray led to presumptive diagnosis of congenital TB. Postnatal acquired TB was less favored due to early presentation of TB symptoms and a fourth criterion of Cantwell et al. was achieved. Thapar et al.7 also reported a neonate with congenital TB presenting as sepsis syndrome. Congenital TB has a very high mortality rate, and those presenting before 4 weeks have mortality up to 50%.2,5,9,11 In spite of difficult diagnosis, clinical suspicion and family history support diagnosis of congenital TB and precocious diagnosis avoids death in infancy period. In our case, the child after antibiotic therapy and oxygen support at a private hospital showed no resolution of symptoms and as soon as the ATT was initiated on the day of admission, respiratory distress and acceptance to feed improved within a week. For more than 60% of cases of perinatal TB, maternal TB disease was diagnosed after it was found in children.9 Extra pulmonary, miliary, and meningeal TB in mother are the high-risk factors for congenital TB in neonates.12 In this case, the mother was diagnosed as a case of neurotuberculosis when the baby showed evidence of recovery.

CONCLUSION

Congenital TB continues to be an unusual diagnosis in pediatric patients. The nonspecific nature of the disease in the newborn infant and the lack of knowledge of the maternal disease prior to delivery make the diagnosis a clinical challenge in both pre- and postnatal periods. The disease should be suspected in neonates that present respiratory distress, fever, and hepatosplenomegaly in the first 3 months of life; neonates with suspected sepsis not responding to routine antibiotic therapy where a bacterial or viral etiology have been excluded.10 In summary, there is a need to improve screening to identify and treat active TB in the prenatal period, which not only decreases perinatal mortality but also prevents the occurrence of this serious disease in neonate and a coherent system of cooperation between the hospital and community services, and between pediatricians and adult physicians is essential.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

CONTRIBUTORS’ STATEMENT PAGE

Dr Karuna Thapar conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed, and critically revised the manuscript. Dr Angie Garg collected data, carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Both authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

REFERENCES

1. Starke JR, Smith MHD. Tuberculosis. In: ed. JS, Remington JO, Klein ed. Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant.Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 2001; pp.1179-1197.

2. Hassang G, Qureshi W, Kadri SM. Congenital tuberculosis. JK Science 2006;8(4):193-194.

3. Pillay T, Sturm AW, Khan M, et al. Vertical transmission of mycobacterium tuberculosis in KwaZulu natal: impact of HIV-1 co-infection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8(1):59-69.

4. Skevaki CL, Kafetzis DA. Tuberculosis in neonates and infants: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management issues. Paediatr Drugs 2005;7(4):219-234. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200507040-00002.

5. Cantwell MF, Shehab ZM, Costello AM, et al. Brief report: congenital tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 1994;330(15):1051-1054. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404143301505.

6. Adhikari M, Pillay T, Pillay DG. Tuberculosis in the newborn: an emerging disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1997;16(12):1108-1112.

7. Thapar K, Dhawan G. Congenital tuberculosis presenting as sepsis syndrome. Pediatr Oncall J 2006 August 1;3:28.

8. Vallejo JG, Ong LT, Starke JR. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of tuberculosis in infants. Pediatrics 1994;94(1):1-7.

9. Hageman J, Shulman S, Schreiber M, et al. Congenital tuberculosis: critical reappraisal of clinical findings and diagnostic procedures. Pediatrics 1980;66(6):980-984.

10. Nakbanpot S, Rattanawong P. Congenital tuberculosis because of misdiagnosed maternal pulmonary tuberculosis during pregnancy. Jpn J Infect Dis 2013;66(4):327-330.

11. Beitzke H. Uber die angeborene Tuberkulose Infektion. Ergeb Ges Tuberk Forsch 1935;7:1-30.

12. Bruchfeld J, Aderaye G, Palme IB, et al. Evaluation of outpatients with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis in a high HIV prevalence setting in Ethiopia: clinical, diagnostic and epidemiological characteristics. Scand J Infect Dis 2002;34(5):331-337.

________________________

© The Author(s). 2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and non-commercial reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.